NEWS

Gumi Backs Dialogue with Bandits as Sani Warns of Failure

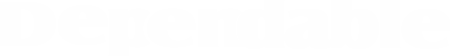

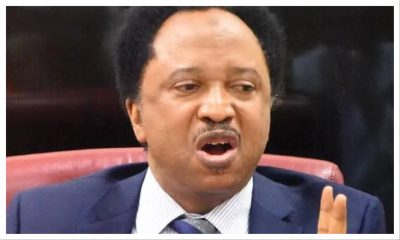

In a deeply polarized debate over Nigeria’s persistent banditry crisis, prominent Islamic cleric Sheikh Ahmad Gumi has once again ignited a firestorm by advocating for dialogue and peace agreements with armed groups in Katsina State. Gumi, a long-time proponent of negotiation, has urged government and security agencies to protect the “fragile truce” in ongoing peace talks, arguing that the armed groups should be treated with the same reintegration approach once adopted for Niger Delta militants. However, his position has been met with fierce opposition from former senator and rights activist, Shehu Sani, who argues that rewarding notorious bandits with dialogue is not only unjust but also a failed strategy that will only lead to further bloodshed.

The latest push for peace talks comes on the heels of reported settlements in Matazu, Faskari, and Sabuwa local government areas, which have reportedly involved several wanted bandit kingpins. In a public statement on his social media page, Gumi celebrated the development, writing: “Alhamdulillah. News has come that today, Sabuwa Local Government has also held a peace settlement with the bandits in the forests to establish peace throughout the entire local government area… May the security agencies avoid destroying this peace agreement but instead teach them how to live in peace, just as was done with the Niger Delta militants.” Gumi’s comparison of bandits to the Niger Delta militants is a key part of his argument. He believes that since bandits are primarily motivated by economic desperation rather than a rigid ideology, they are capable of being rehabilitated and reintegrated into society through amnesty, education, and skill acquisition programs. He points to the Niger Delta Amnesty Program, which saw a significant reduction in violent activities and a surge in oil production, as a viable model, even while acknowledging its flaws.

The cleric’s proposition, however, is not without its critics. Former senator Shehu Sani, a consistent voice against negotiation, has strongly condemned the initiative. Sani argues that treating mass murderers and kidnappers as legitimate negotiating partners is morally bankrupt and an insult to the victims of banditry. He believes that past failures of similar peace deals in Katsina and Zamfara serve as a stark warning. According to Dependable NG, past deals collapsed primarily because of the fragmented nature of banditry itself, which consists of dozens of rival gangs with no central command structure. A peace agreement with one faction does not guarantee the others will stop their attacks. Sani insists that justice, not negotiation, is the only sustainable solution. “Bandits who have killed thousands, kidnapped innocent people, and raped women should not be rewarded with dialogue. They should be prosecuted or outrightly eliminated,” he said, stressing that any form of appeasement only emboldens them.

The historical context of banditry in Northwest Nigeria further complicates the debate. The crisis, which escalated around 2011, is rooted in a combination of factors, including a decades-long competition for resources between herders and farmers, widespread poverty, and the discovery of gold in Zamfara. The absence of effective government and security presence in vast forested areas has allowed these criminal enterprises to thrive. The bandits’ modus operandi—kidnapping for ransom, cattle rustling, and extortion—is fundamentally a business model. This has made them an intractable problem for both the federal and state governments, which have alternated between military operations and peace talks. However, the military approach has often been hampered by the bandits’ highly mobile tactics, while the dialogue option has been undermined by their deceitful nature. In the past, bandits have repeatedly broken their vows, even after swearing on religious texts, which has eroded trust and led to accusations that these talks are simply a ruse to get paid off or rearm.

As the debate rages on, the communities in the affected areas remain trapped between two conflicting approaches. While some, out of desperation, are willing to engage in local agreements to buy temporary peace, others remain steadfast in their belief that the government must protect them and hold the criminals accountable. The ongoing peace talks in Katsina are a litmus test for the effectiveness of dialogue as a solution. The outcome of these talks will either validate Gumi’s long-held position that rehabilitation is possible or reinforce Sani’s warning that appeasement is a dangerous illusion. The Nigerian government, caught in the middle, must navigate this difficult terrain to find a lasting solution to a crisis that has claimed thousands of lives and displaced countless others.